First and Second-Order Epistemologies

Gregory Bateson (1991) famously said that we “cannot claim to have no epistemology. Those who so claim have nothing but a bad epistemology” (p. 178). Bateson is calling for self-reflection in our epistemology. He wants it to be recursive, so that in our production of knowledge we do not delude ourselves into thinking that the means of production is independent of what is produced. Bradford Keeney, cybernetic epistemologist, family therapist, modern day New Orleans-style shaman, and student of Gregory Bateson, notes that recursive epistemology has roots in second-order cybernetics and the recognition (1983) that “any distinction drawn is drawn by an observer. … An observer observes by drawing distinctions. … The starting point of epistemology is therefore an observer drawing distinctions in order to observe” (p. 24). This leads us to a fundamental recursion or non-linearity at the very start of any epistemological endeavor. While non-recursive epistemologies try to mitigate this kind of loopiness, cybernetic epistemology embraces it as the very heart of knowing, using it as a creative generator of change and transformation. Working with a non-lineal epistemology leads to a different kind of knowing, one which “emphasizes ecology, relationship, and whole systems. In contrast to lineal epistemology, it is attuned to interrelation, complexity, and context” (Keeney, 1983, p. 107).

The consequences of lacking a self-reflexive epistemology are dire, leading to real practical and ethical dilemmas. The structure of the sequence often goes something like this:

- Knowledge is produced on the basis of a non-reflexive epistemology (Bateson’s “bad” epistemology). Ex: You performed an act found to be illegal.

- The knowledge produced is thus assumed to be “objective” and “true” (i.e. independent of the means of its production; ignorant of its genesis). Ex: It doesn’t really matter why you did what you did, you are beholden to the law as written.

- This tends to have a psychologically limiting effect with respect to alternative knowledge and especially alternative modes of knowledge production. One’s viewpoint becomes ossified. Ex: The judicial system limits its treatment of you as a whole human being only to what is allowable within the strictures that the law defines. You become identified with your act.

- The unreflective assumption of the “truth” of the knowledge becomes justification for its projection, often forcefully, onto other people and processes in the environments surrounding the knower. A sense of conviction that the world is “like this” leads to inflexible protocols in our institutions and in our modes of interaction with others. In other words, outer processes are also ossified; they become sclerotic. Ex: Now, instead of being a whole human being who with a completely full and complex life that included the illegal act, your identity shifts to that of a criminal. Your identity shifts, and you are now identified with the label “criminal,” and the judicial system creates places called prisons designed largely to maintain this distinction of your new identity.

The unintended effects of this kind of lineal process knowledge production could fill multiple volumes, from the most subtle aspects of daily life to world-historical events. But recursive epistemology is not in opposition to lineal epistemology; it is rather meant to be a way of maintaining complexity and subtlety (and ideally, wisdom) by calibrating the linearity of standard epistemological practices through higher-order recursion.

Calibration and Self-Calibration.

But what does it mean to have a self-reflexive epistemology? The difference between the two types of epistemologies, non-self-relfexive and self-reflexive, can be described by the first and second order difference. A non-self-reflexive epistemology is a first-order epistemology, a process of creating knowledge that operates in a linear fashion. The knowledge it generates is not explicitly connected to the process of its generation, and thus does not act as a potential corrective to its mode of production. Epistemology is a tool for knowing; but with a non-self-reflexive epistemology, the tool’s operation does not change the tool, so that no matter what job it is called to do, it re-instances any new creations in the manner and style of its past processes—regardless of what might be new in the situation it encounters. The kind of newness that comes from a linear epistemology is innovative, but not radical. It is well-suited to the kinds of knowledge domains that work towards technical, but not paradigmatic, advances.

To use a term from cybernetics, a linear epistemology is resistant to calibration (higher order feedback). But this lack of openness to calibration is often not simply passive, but active: attempts at calibration are often either discarded or met with increasing rigidity, with a sort of “doubling-down” on the knowledge already produced by the epistemology, and an increasing unwillingness to change the process by which knowledge is produced. We could therefore describe this kind of epistemology as willfully ignorant. This can actually be quite beneficial in producing new knowledge (within the parameters already accepted by the epistemology), because it minimizes the recursive complexity and is more amenable to simplification. Reductionisms of all types, where all phenomena, regardless of their complexity, are explained only in terms of more simple (and often more abstract) entities, are linear epistemologies. Said differently, a linear epistemology allows one to ignore second-order alternatives. Most of modern scientific thinking rests on the back of linear epistemology, to which it is well-suited.

On the other hand, a self-reflexive epistemology is a second-order epistemology (see the table at the end of this post for a comparison of qualities — with images!). The process allows itself to be changed by the content it produces. It is thus an open epistemology that operates on the basis of a recursion between process and content. It is open to calibration, and not simply in a passive way, but actively: it seeks calibration of its own processes (not just its content) through an active monitoring of what it is generating. Whereas a linear epistemology tends to minimize calibrative influences (changes in the way it operates at a second-order level), a recursive epistemology actively embodies them at its heart; it is not merely open to calibration, but is self-calibrative. The linking of process and content in this recursive way is akin to the creation of a new type of sensitivity; we can metaphorically say that operating with a recursive epistemology is the development of a new type of higher sense-organ for a knowing system. This is another way of saying that what a system distinguishes distinguishes its distinguishing. Recursive epistemology is open to self-revision not only at the content level (which is also true of linear epistemologies, although there may still be a difference in their relative inertia to this change), but also at the process level. This means that the kind of newness it can potentially yield includes radical, as well as technical shifts. Radical shifts restructure the further possibilities that are available to the knowing system; they are paradigmatic shifts.

What is important to consider is that the recursion between knowledge and knowing (between content and process) actually applies to all epistemologies, even first-order epistemologies. It is simply that in the case of a first-order epistemology, the epistemology is not systemically inclusive of this fact; we could say that it is not sensitive to its own sensitivity. A second-order epistemology is sensitive to its sensitivities: it includes processes whose content is the change of processes. The most tightly recursive epistemologies have processes whose content is itself. We will see later that differences in the level of tightness in the recursion has consequences for how we can think about esoteric practices such as meditative visualization.

The Unknown and Unknowing.

Every epistemology has its boundary, a place where it meets a kind of threshold of what it can so far distinguish to itself. Here again we have a first and second-order difference. The first-order level to this threshold is the possible content that could be revealed there, if only our knowing could continue across the threshold. This is the unknown, as a content. The second-order level to the threshold is the ongoing activity of the unknowing.

A first-order epistemology meets its boundary only by virtue of the loss of what is seen as its potential content. The unknown is assumed to be a specific content that is just like the known in every way except that has yet to be brought to light, discovered, or found. These metaphors work from the assumption that knowledge is somehow waiting “out there” to be had, and the protocols for knowledge production are thus geared towards the transformation of the unknown into the known, often with forceful manipulation and through maximization of control procedures. The unknown is precisely what needs to be minimized, and processes that generate unknowing are therefore seen as barriers to further knowing, leading only to confusion or obfuscation. The unknown is valued only negatively, as the not-yet-known. The not-yet-known is pulled through from the other side of the threshold and brought “down” to re-instance the same reality that the epistemology already operates within, as further proof of its existence.

A second-order epistemology meets its boundary also by virtue of what is not known, but in addition it values the unknowing as an active and potentially transformative process. What for the first-order epistemology is only a potential new content is for the second-order epistemology a potential new way of being. This is a higher-order content, and is not simply “out there” to be discovered but must be enacted to exist; it must be brought into being. The unknowing is thus taken to be an invitation, a doorway, and instead of taking the unknown and making it known through the same epistemological patterns, it opens the door to more unknowing.

Enacting a second-order epistemology is to allow one’s way of knowing to change, not just the content of what is known. Unknowing is thus valued as a transformative agent, as a source of not only new knowledge but new ways of living forward. For a second-order epistemology, unknowing is a feature to be actively worked with, even developed, rather than a bug to be squashed. Said another way, a linear epistemology does not know that it does not know, while a recursive epistemology does, and makes of this something new of itself. The active incorporation of processes that yield states of unknowing is a primary way that a recursive epistemology self-calibrates.

Validity.

[[This discussion is meant to provide a re-orientation at a process level of what is meant by the terms thinking, thought, world, and reality. Following Gendlin (1991), the terms mean how they are used in the context of these sentences, and the sentences are formed to indicate what the words mean. If the words are taken to carry only their old, habitual meanings, then the passage will not make any sense; new meanings are being brought forth in their usage in this way, here in these sentences.]]First-order epistemology focuses on the content of what it produces, and derives from this content the very justification for its truth; it invests its validity in its facts. This is an important but subtle and difficult point: a linear epistemology generates facts, and then projects them onto “the outer world” (which is created for us in this projection) so that when we perceive the world we derive a sense of certainty about our epistemological relationship to it. The world seems simply to be that way—the projection of our thoughts onto the world obscures our thinking. We ask the world to tell us what we can know, without realizing that we have given the world the ability to speak to us when we dissolve our thinking in it, leaving only thoughts behind as a kind of corpse. By investing the world with our thoughts, we give it the power to reflect back to us—as if independently of our activity—“the known.” Thus the validity of a linear epistemology is felt when we discover its results in the facts “out there,” because for such an epistemology the facts mark the epistemological end-point, the place where thinking is no longer required, where it dissolves itself in the projected object of its knowing. What is left behind is a thought-content, which, divested of its genesis, seems to exist independently of us, providing a powerful sense of certainty. Linear epistemology thus often perceives the world as intrinsically dead, not living. It is objective, and has existence only as objects, independent of any subjects. But when dead objects are taken to be fundamental, this kind of view tends to produce deadening and objectifying modes of interaction with the world. We need only look to any of the innumerable modern crises in the environment, in politics, in education, in medicine, and elsewhere to see the kinds of effects the adoption of this kind of epistemology produces.

A critic will respond to this by pointing out that the truth of the knowledge discovered by a linear epistemology is not dependent on the knower, because it can be utilized to achieve the production of technological objects that work independently in the world. Technological devices—cell phones, transistors, steam engines—are taken to demonstrate the veracity of the epistemology because the technologies work. If the epistemology was in error, technologies could not successfully be developed from the principles it discovered (it is assumed). All standard scientific prediction follows this same epistemological pattern: the test of knowledge is found in its empirical demonstration, in whether it yields some particular configuration of “outer events” vs. another. If our theory predicts that we observe state A in the world, and then we look at the world and observe that it is in state A, we feel justified in assuming that our theory of state A actually applies to the world. What could be wrong with this?

The more subtle view of recursive epistemology sees that we project our thought about state A onto the world through the activity of our observation of it; this is why “outer events” had to be put in quotes in the previous paragraph. The activity of observation ceases, but the thought content left behind now makes “reality” appear for us as such. If reality is taken to be a piece of glass, our thoughts form the silver coating on its back that reflects the activity of thinking back to itself, so that it can perceive a world, and itself in that world. Thinking thus perceives its thoughts in the world, but it does not perceive its own activity, to which it is asleep (at first). We could say that the world—the world in which we actually live forward, not an abstract world-without-us—is the perceiving of our thoughts projected there by, and reflected back to, thinking. When the process is non-recursive, the result leaves us with the sense of a world that just “is” that way; allowing us to take it for granted as such. Thinking’s projection of itself as thoughts into the world allows itself to forget itself as thinking; it sees itself only reflected in its thoughts. Thus the “discovery” of the properties of the world is also the discovery of our thoughts in it, but not necessarily the discovery of thinking: something more is required for that. Recursive epistemology is a way of describing this something more, and an invitation to enact it.

With this background, the argument about technology demonstrating the truth of the knowledge derived from a linear epistemology can be seen in a different light. When we create a new technology or empirically test a scientific theory, we are actively involved in the linking of a thought-content to the world (remembering that the world arises for us in this activity). When this linking is hidden by the very process of the linking itself, it seems as if “the world” validates the underlying principle in question. Nothing more seems required; state A was predicted, state A occurred, case closed, further thinking can be avoided, and the process can now be given over to the engineers for implementation. This is a dangerous tendency for linear epistemologies, because it covers over its assumptions with a profound feeling of the correctness of the thought. Good science already knows that correlation is not causation; but the point here is that even causation is not causation. This is another sentence that is meaningless unless it is taken from a perspective that can distinguish between first and second-order meanings.

Hume, of course, raised a similar point using a very different set of concepts in his An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1938), where he notes that “nothing is more usual than to apply to external bodies every internal sensation which they occasion” (p. 57). Hume understood projection, and the problems it raises for inductive thinking and causation, but from a first-order level. When we recognize the second-order relation between the activity of thinking and the thoughts that precipitate out of thinking as its product, the door is opened for a different kind of relation between thinking and the world, based not upon the linear polarities that result from a first-order epistemology (I/world, subjective/objective, illusion/reality, etc.), but which rest on a recursive foundation in which such polarities are always parts of larger circles. This is what Jung (1972, pp. 72–73) identified, in his own way, with his psychological conception of the enantiodromia, a term which goes back to the process-philosophy of Heraclitus, concerning the union of opposites; more on this later.

When considering the source of its veracity, a recursive epistemology walks a delicate middle line. It does not project itself onto the products of the stopping of its own activity (the dead object), but it also does not move to the extreme of pure solipsism, where the world becomes somehow ‘simply’ my creation. It rather works with the arising of truth out of the relating between process and content, between a first and second-order recursion. It takes neither the world nor the knower for granted as such, and seeks a phenomenologically oriented integration of knower and known through their recursive relating. In a linear epistemology truth is taken at a first-order level. Indeed, the very strength and power of first-order epistemology is its self-enclosing of truth within processes that yield first-order content amenable to the kind of projection that is only noted from a second-order level, as just discussed. Looked at from the second-order perspective, truth for a linear epistemology is limited to what can be adequately projected outside the processes that yield it (another basis for its willful ignorance).

A consequence of this is that linear epistemologies tend to produce knowledge in piecemeal form. Truth occurs in bits, the veracity of which is not intrinsic to the bits, but only supported by the truth of other, immediately adjacent bits. This conception has led to the development and continued reduction of knowledge into specialties, sub-specialties, and sub-sub-specialties. Although alternatives to this trend have always existed (notably in some “esoteric” and aesthetic domains, including anthroposophy), it is only relatively recently that its limits have been increasingly recognized from within the various disciplines. The recent rise of transdisciplinary thinking (“Ngram for the word Transdisciplinarity,” 2012) is in part a result of this recognition, and is an attempt to frame debate about these limits in a transformative way. Transdisciplinarity is a seeking of a way forward that does not require a wholesale break from past knowledge and processes of knowledge construction. It wants to carry forward the vast amount of knowledge they have produced, but in ways that do not recapitulate the epistemological and ontological blindnesses of their second-order processes.

It is not a question of whether one or the other epistemology is “right” – at least in the sense carried by this question when asked from a first-order perspective. A consequence of recognizing the importance of the role of second-order recursion in epistemology is that it re-orients the focus of epistemology in a profound way. A recursive epistemology loses its ability (derived from first-order thinking) to keep itself separate from the bigger picture, through which it integrates itself in a transdisciplinary way with other fields, such as ontology, cosmology, aesthetics, and so forth. Recursive epistemology is not merely about knowing and how we think, but also about how we act, how we feel, and how we live ourselves forward with the world, in recursive relationship with it. This is what allows the knowledge it produces to be not just about parts (although it is also about parts), but about wholes. It understands that knowledge is never separate from a knower, and that a knower is never separate from all the wider contexts in which knowing occurs. Thus a very important question for a recursive epistemology is what are the wider contexts? But that phrasing is old, and still carries the assumptions of linear epistemology, and we are looking for something else.

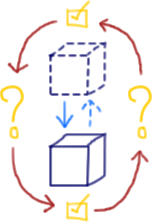

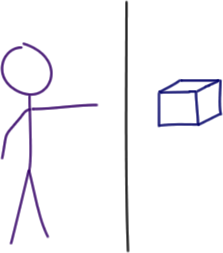

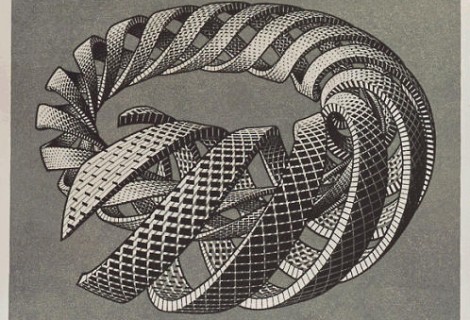

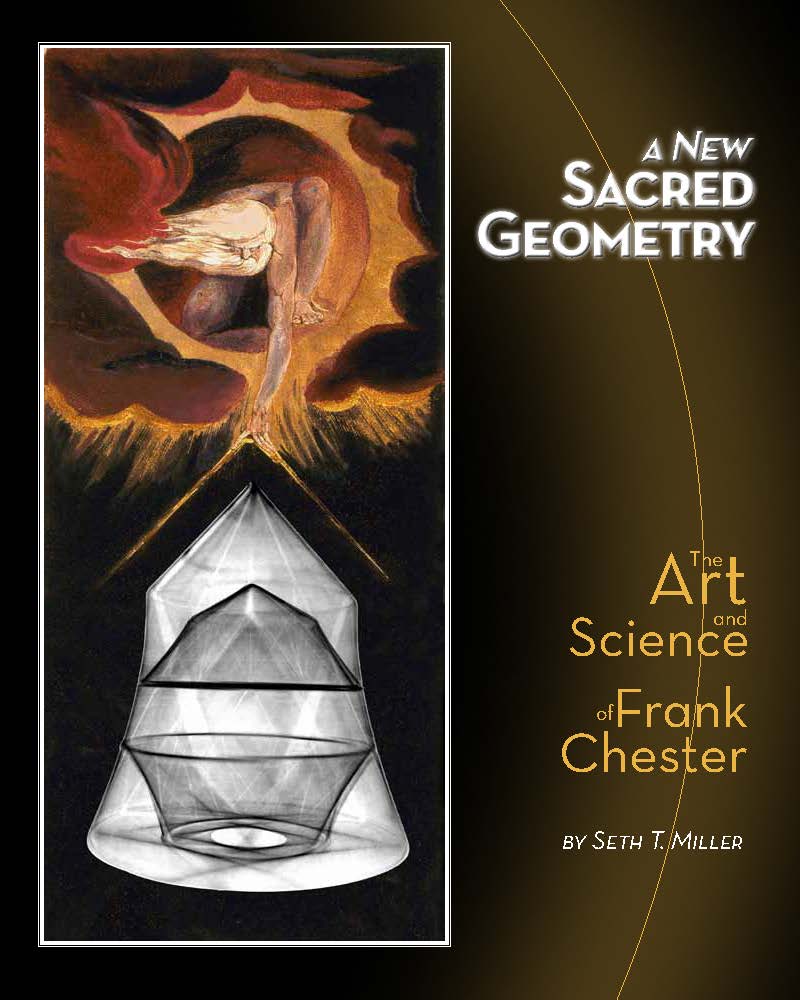

It is enough at this stage to note these major differences between first and second-order epistemologies. Table 1 adds gesturally-oriented images to the differences between linear and recursive epistemologies. Many other images could be made to indicate the same differences.

Linear Epistemologies |

Recursive Epistemologies |

|

|

|

References

Bateson, G. (1991). Sacred unity : Further steps to an ecology of mind (1st ed.). HarperOne.

Gendlin, E. (1991). Thinking beyond patterns : Body, language and situations. The Focusing Institute. Retrieved April 18, 2012, from http://www.focusing.org/gendlin/docs/gol_2159.html

Hume, D. (1938). An enquiry concerning human understanding. Forgotten Books.

Jung, C. G. (1972). Two essays on analytical psychology. (G. Adler & R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton University Press.

Keeney, B. P. (1983). Aesthetics of change. New York: Guilford Press.

Seth, this is a very concise, pithy statement of the web of “residues of unresolved positivism” (Barfield) that entangles modern consciousness. Steiner calls this “the dragon” but challenges us to also become aware of the presence of forces of Michael in our consciousness, though which we can slay/tame this dragon.

Next, we’ll work on an equally concise statement of the experience of first steps in freeing ones-self from this entanglement…

Thanks for posting this!

Great pictures; thanks for posting!