Consequences of the discovery of perspective in art

The “discovery” of perspective was a radical point (pardon the pun) in the development of art, and was intimately tied in with a whole shifting of consciousness during the time of the Renaissance and forward, having correlative expressions in the increasing reliance upon an “objective” perspective from which to view the world. Science in its modern form arose during this period as a methodological way of systematically removing subjectivity from observations, allowing data to be gathered which was amenable to enumeration and mathematical manipulation. The abstraction of the observer from the observed and the dissociation of both this abstracted observer and the observed phenomenon from the ever-changing background contexts that held both provided a powerful basis for a new way of being in the world.

The laws of perspective allowed the world to be visually reduced, literally, to a point. Each point became a point in space from which the world looked a certain way, and the way it looked from one point always differed from the way it looked from any other point. It is interesting to note that the laws of perspective, designed as a basis from which visual scenes could be rendered on canvas in a way that accurately captured the “real” experience of our visual sense, required a reduction of the very visual experience it was meant to uphold. What I am referring to is the fact that perspective works from a single point, but the human being experiences the world through TWO such points. The laws of perspective required the literal and figurative shutting out of fully half of our visual experience.

Truth thus became as one-pointed as perspective drawing, subject to the perfect and known limitations of a small set of rules; all deviations were to be ‘explained away’ by recourse to the completely non-personal operation of blind forces. In art, ANYONE could presumably have the exact same visual experience as the next person if they stood in just the right spot at the right time; it took no special training or knowledge to interpret what was seen, because what was seen was reduced to its primal base: form and color in strict, law-abiding combinations. Ironically, the point, a completely abstract dimensionless non-entity, set the tone for our experience of all the dimensions of available to our experience.

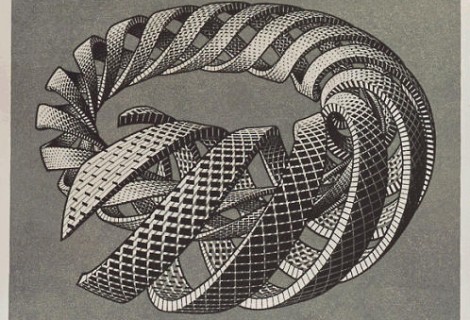

Ultimately, however, this perspectival program was destined to destroy itself through its search for perfection. In art, the quest to represent visual experience led beyond form and color to the wider and fuller experience of vision as a whole. Many figures, from Goethe to Picasso, took part in a constructive dismantling of the dominant paradigm. In science, this occurred through the discovery of relativity and quantum mechanics, and later chaos theory, which banished forever the naïve reliance upon the point-like structure of previous generations.